First-Ever Video Footage of Stealthy Black Hawk Helicopter Emerges

A Decade of Secrecy Unveiled: The Stealth Black Hawk’s Hidden Lineage

It has been almost a decade since the world first learned about the covert use of stealth Black Hawk helicopters during the daring Bin Laden raid. Since that time, we have seen no images or heard about their lineage—until now.

Our quest for information regarding the U.S. military’s enigmatic stealth Black Hawk helicopters has been unrelenting. These helicopters, one of which famously crashed during the raid that resulted in the demise of Al Qaeda’s leader, Osama Bin Laden, in 2011, have remained shrouded in secrecy. We have sought not only to uncover more about the stealth Black Hawks used in the Bin Laden operation but also to trace their possible precursors that existed before them. Now, an intriguing discovery has come to light—a previously unpublished photograph showcasing a heavily modified EH-60 electronic warfare and signals intelligence variant of the Black Hawk. This image appears to bridge the gap between the unique Black Hawk helicopters used during the Bin Laden raid and the stealthy Black Hawk design concepts that date back to the 1970s.

The photograph in question, shown at the top of this article and below in an enhanced format, is linked to Fort Eustis in Virginia. Fort Eustis, home to the 128th Aviation Brigade, formerly known as the U.S. Army Aviation Logistics School, and Fort Eustis’ Felker Army Airfield, is where the enigmatic Flight Concepts Division (FCD), now called the Aviation Technology Office (ATO), is located. This unit is widely believed to be responsible for spearheading the development of the stealth Black Hawks used during the Bin Laden raid and many of the U.S. Army’s most advanced and secretive rotary-wing capabilities.

The exact date of the photograph is unknown, and there is limited information available about the helicopter’s associated program or programs. The photo was taken in an unidentified desert location, possibly somewhere in the American Southwest, which is home to numerous aviation test facilities, including top-secret air bases like Area 51 and the Tonopah Test Range Airport, where the stealthy Black Hawks from the Bin Laden raid were reportedly housed.

The helicopter features four dipole antennas, two on each side of the tail boom, a common characteristic of both the EH-60A and EH-60L. Under the fuselage, it appears to have the long, retractable whip antenna found on the EH-60A, as opposed to the more robust antenna system on the EH-60L. This central antenna is associated with the AN/ALQ-17A(V)2 Trafficjam communications jamming system, part of the larger Quick Fix II suite.

In addition, the helicopter boasts two large missile approach warning sensors, one on each side of the nose, situated beneath the main cockpit doors. These sensors are part of the AN/ALQ-156A Missile Approach Warning System (MAWS), found on both EH-60As and EH-60Ls. Two identical sensors were also mounted well behind the fuselage doors, offering 360-degree coverage. The EH-60s were eventually equipped with a version of the AN/APR-39 radar warning system, as were other Black Hawks, featuring smaller receivers on the nose and tail of the helicopter.

One noteworthy feature of this helicopter is its stub wings, providing a hardpoint on each side. These wings are more commonly associated with MH-60L/M Direct Action Penetrators assigned to the U.S. Army’s elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment and U.S. Navy MH-60S Seahawks. The External Stores Support System (ESSS) wing kit, featuring two hardpoints on each side, is far more common.

The most striking modifications are found in the helicopter’s nose, the “doghouse” housing the engines and main gearbox, the engine intakes, exhausts, and the rotor hub—all designed to reduce its radar signature, particularly from the critical forward hemisphere aspect.

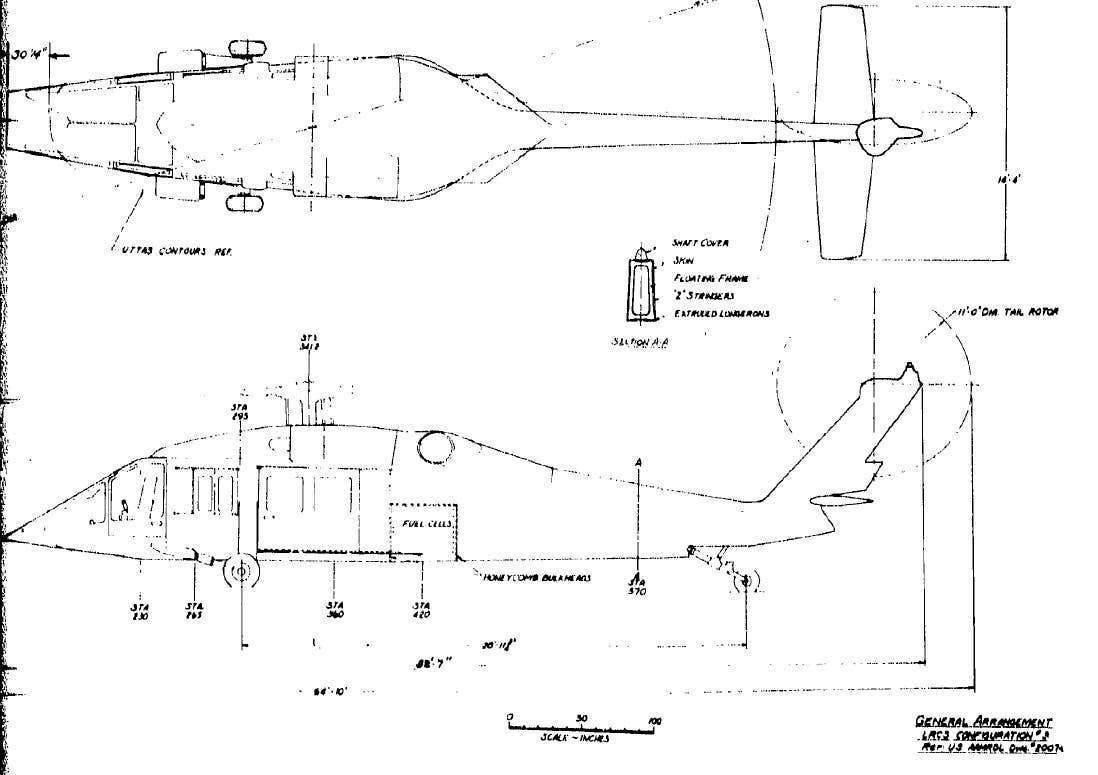

The duckbill-like nose bears resemblance to stealthy design concepts that Sikorsky crafted in 1978 for the U.S. Army Research and Technology Laboratory, a unit at Fort Eustis. This extensive study was the first indication of the Army’s interest in a reduced-signature Black Hawk.

Additionally, the nose, doghouse, and rotor hub display visual similarities to a kit developed by Bell for the OH-58X Kiowa in the 1980s, as detailed in a previous report. Bell’s kit incorporated similar concepts into the OH-58X, although the Army evaluated, but did not widely adopt the OH-58X, opting instead to procure a number of stealthy kits for its OH-58D Kiowa Warrior armed scout helicopters.

Sikorsky proposed using advanced radar-absorbing composite materials in its stealthy Black Hawk design studies in the late 1970s, while Bell applied similar concepts to its OH-58X. Sikorsky also experimented with its S-75 technology demonstrator in the mid-1980s, which made extensive use of composites and informed the development of the aborted Boeing-Sikorsky RAH-66 Comanche. The Comanche also featured a complex shrouded rotor hub design similar to the one on this particular Black Hawk. It is highly likely that many, if not most, of the additions to this EH-60 were also constructed from composites to enhance radar signature reduction and manage the additional weight added to the helicopter when installed.

Notably, the modified engine intakes on this Black Hawk appear designed to conceal the fan faces of its two turbine engines and significantly streamline the area around the engine nacelles and forward doghouse region. These modifications aim to minimize radar reflectivity, as traditional designs are known for their high radar reflectivity.

In contrast to the helicopters used in the Bin Laden raid, this particular example lacks tail rotor modifications that would have negatively impacted its all-aspect radar reflectivity and acoustic signature. However, the helicopter’s front aspect would have been the most critical concern for radar stealth, especially when infiltrating heavily defended areas. Whether additional stealthy add-ons for the tail were developed later for this project or not installed in this specific instance remains unknown.

Without identifying the particular EH-60 variant, it is challenging to pinpoint the date of the photograph. Sikorsky began developing the EH-60A for the Army in 1980 after the service decided against deploying the Quick Fix II system on a variant of the venerable Bell Huey helicopter, known as the EH-1X. The EH-60As eventually replaced older EH-1H helicopters equipped with the AN/ALQ-151 and AN/ALQ-151(V)1 Quick Fix suites.

Between 1989 and 1990, work commenced on the Advanced Quick Fix system, originally intended for another UH-60A variant, known as the EH-60C. The Army ultimately decided to install it on a modified UH-60L, taking advantage of the more powerful engines of this variant, which became the EH-60L. It is important to note that this EH-60L configuration should not be confused with EUH-60L helicopters configured as airborne command posts. The Army ultimately did not proceed with the Advanced Quick Fix system on a widespread basis, a fate that befell many U.S. military programs in development during the time of the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991.

Based on the available information, it is plausible that the photograph was taken in the late 1980s or, more likely, the 1990s. This timeframe aligns with Sikorsky’s collaborative efforts with Boeing on what would become the RAH-66, though the exact relationship between these two initiatives remains unclear.

The use of an EH-60 in this case might have simply resulted from the availability of this particular helicopter for testing purposes. The small EH-60 force is known to be utilized for various tests and modification trials. It is also important to note that reports have long suggested that the stealth Black Hawks used in the Bin Laden raid were equipped with a “snap-on” type kit, but the tail of the crashed helicopter appeared to be far too elaborate for a temporary modification.

There is also the possibility of confusion regarding the extent of work on stealthy modifications to the Black Hawk at the time of the historic raid. These helicopters were an exceptionally well-kept secret, and we might never have learned about them if it were not for the crash. Pentagon officials may have misconstrued older tests involving more basic kits with a far more elaborate configuration used in the actual raid.

It is also possible that the Army may have been interested in developing a stealthy kit for broader use on its Black Hawks, and this photo represents one version of such a solution. Integrating these features specifically into the EH-60 variants could have been a more focused effort. Reducing radar signature could enable these platforms to approach their targets without detection and subsequently jam them, creating pathways for non-stealthy helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft to follow.

A kit that could be added and removed from any Black Hawk variant as needed would be an effective way to avoid unnecessary exposure of the capability during routine operations. Any performance degradation would not be permanent, allowing the helicopters to operate in a standard configuration at other times.

Finally, the most pressing question remains: could these modifications be the same as those used on the Bin Laden raid helicopters? Clearly, the tail of this example received nowhere near the same treatment. It is possible that a kit exists that combines these forward elements, or very similar ones, with a far more elaborate tail assembly designed to reduce acoustic signature as well. While this is possible, our best estimation at this point is that this configuration represents an evolutionary stepping stone or an earlier iteration of what ultimately led to the now-famous but never-seen ‘Stealth Hawks.’ Only those who are forbidden from discussing the matter on the record truly know for sure.

In the past, we have been told that the Stealth Hawks were based on the MH-60 platform, with an outer composite body specifically built by Sikorsky to accommodate the modifications. We have yet to corroborate these claims. It is also stated that newer and more complex generations of the Stealth Hawks were built after the Bin Laden raid and are currently in service.

It is astonishing that almost a decade has passed since the daring mission into Abbottabad, yet we remain without additional official information about the helicopters used, with no sightings of similar platforms. Perhaps the most accurate description of the aircraft came from Robert O’Neil, often controversially referred to as ‘the man who killed Osama Bin Laden.’ He recounted the following in the weeks leading up to the raid:

“When we got to Nevada a few days later, where the team trained on another full-scale compound model, but this one crudely fashioned from shipping containers, we turned the corner, saw the helos we’d actually use, and I started laughing. I told the guys, ‘The odds just changed. There’s a 90 percent chance we’ll survive.’ They asked why. I said, ‘I didn’t know they were sending us to war on a [expletive] Decepticon.'”

Now, thanks to this image, we finally have concrete evidence of what at least one version of a ‘Stealth Hawk’ looked like, and the term ‘Decepticon’ seems fitting.

We have already contacted the Army for more information about this specific Black Hawk and any details regarding its stealthy features. We will continue to uncover additional information about this helicopter as it becomes available.

Hits: 12