Colin Chapman, the founder of Lotus, once famously stated that the key to making a vehicle faster is to “simplify and add lightness.” While this principle has held true for sports cars and race cars, it is even more applicable to aircraft. Airplanes operate in a three-dimensional space, where every ounce counts, making the quest for lightness and speed all the more crucial. A testament to this philosophy is the remarkable Grumman F8F Bearcat, a World War II carrier fighter that exemplified the concept of making an aircraft lighter, faster, and better.

To fully appreciate the Bearcat’s story, one must delve into the history of its manufacturer, Grumman Aerospace. Founded by Leroy Grumman in 1929 in Baldwin, Long Island, New York, the company later relocated to Bethpage, New York, in 1937. Grumman Aerospace primarily dedicated itself to meeting the U.S. Navy’s growing demand for piston fighters for their expanding fleet of aircraft carriers. The journey began with the FF, affectionately known as “Fifi,” which was the first American-built aircraft with retractable landing gear.

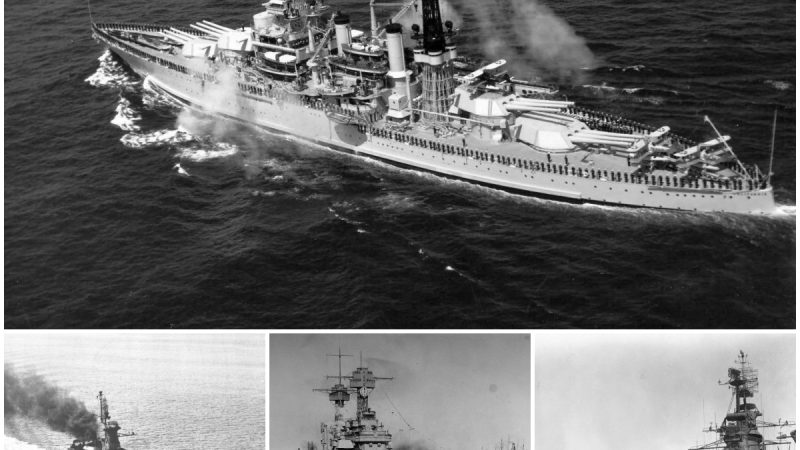

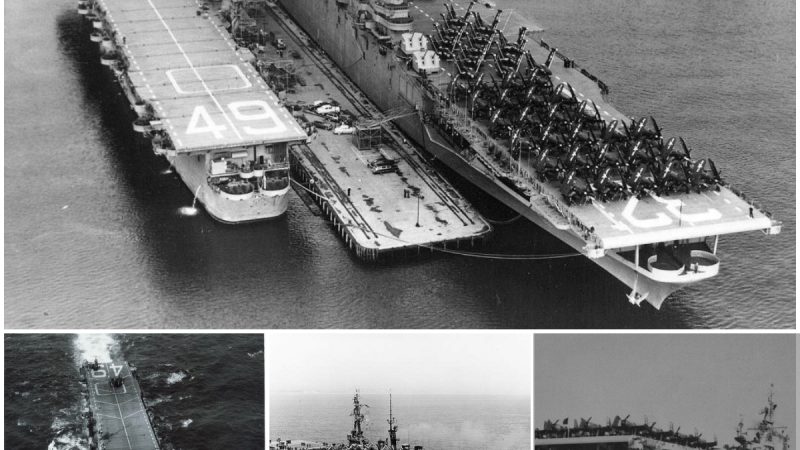

The culmination of this lineage of biplanes was the F3F, marking the end of the era of biplanes in U.S. Navy carrier service. The transition led to the development of Grumman’s iconic “big cat” line of carrier fighters, starting with the legendary F4F Wildcat. The Wildcat, equipped with features like self-sealing fuel tanks and a reliable Pratt & Whitney R-1830 radial engine, admirably defended against the relentless Japanese threat, epitomized by the Mitsubishi A6M Zero. However, the Wildcat’s weight and underpowered engine made dogfights with Zeroes challenging.

Many Wildcats struggled in combat against Japanese Zeros, forcing American pilots into steep climbs that the chunky Wildcat couldn’t sustain, leading to stalls and vulnerability. A drastic solution was needed, resulting in the creation of the F6F Hellcat in 1943. This larger, more powerful aircraft, with its Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engine, rectified the Wildcat’s shortcomings and took on the Zeros effectively.

While the Hellcat might not have had the aesthetic appeal of a P-51 Mustang or a Spitfire, it outperformed them in terms of kill-to-loss ratio. It accounted for over 5,000 enemy aircraft during the war, contributing to a remarkable 75 percent of the U.S. Navy’s aerial victories in the Pacific Theater. As World War II approached its end, Grumman engineers recognized that the era of piston-engine supremacy in aerial warfare was coming to a close. However, they believed there was still room for improvement in the Hellcat’s design.

Even before the renowned advocate of lightness, Colin Chapman, constructed his first race car using an old Austin 7, Grumman was preparing to apply a similar philosophy to the iconic Hellcat. Legend has it that following the Battle of Midway in 1942, a group of Wildcat pilots met with Grumman’s Vice President, Jake Swirbul, in Pearl Harbor. At this meeting, they highlighted the need for a small, powerful fighter capable of taking off from escort carriers, emphasizing the importance of a high horsepower-to-weight ratio.

Internally known as the G-58, Grumman decided to simplify and reduce the cost of this new fighter by slimming down the Hellcat’s basic design. The Bearcat, as it would come to be known, was significantly smaller than the F6F Hellcat, with a shorter length and wingspan. It was nearly a full ton lighter and featured a high-visibility bubble canopy behind the pilot’s seat. Weight-saving measures included reducing the number of machine guns and carrying a lighter fuel load. In the end, the Bearcat was 20 percent lighter than the Hellcat and significantly faster.

On August 21st, 1944, the first prototype XF8F-1 Bearcat took flight over Long Island. It was an absolute delight to fly, with exceptional climbing capabilities that outperformed many other aircraft. Its maneuverability was unparalleled, with a roll rate that could make seasoned pilots feel queasy. The Bearcat was in a league of its own among carrier-based prop fighters, challenging the notion that they were less formidable than land-based fighters.

The Bearcat’s remarkable performance was underscored when it set a record for the time-to-climb from takeoff to 10,000 feet, achieving this in just 94 seconds. On paper, it seemed that Grumman had produced a fighter capable of taking on the air forces of Japan and Germany simultaneously, provided there were enough of them. The British Hawker Sea Fury was the only Allied naval prop fighter that came close to the Bearcat in terms of performance.

However, there was a significant obstacle. By the time the Bearcat was ready for deployment on May 21st, 1945, Germany had already surrendered to the Allies two weeks earlier, with Japan following suit in September of that year. This meant that the Bearcat missed World War II entirely.

Despite a U.S. Navy order for over 2,000 Bearcats, only 770 were produced. Even replacing the Bearcat’s Browning machine guns with U.S. copies of Hispano Suiza HS.404 autocannons in the F8F-1B variant failed to generate significant interest.

The Bearcat’s most prominent role in the U.S. Navy was not in combat but with the Blue Angels aerobatic squadron. In 1951, around 200 Bearcats were delivered to the French Air Force for use in the French Indochina War, where they saw limited combat action. Some were also given to Thailand in 1949.

Today, the Bearcat is best known for its participation in air races worldwide. Notably, a modified Bearcat airframe equipped with a massive Wright R-3350 Duplex Cyclone engine, known as Rare Bear, is considered the most famous air racer in the world. While it may not have recorded aerial victories in combat, its legacy in air racing underscores its significance as one of the most important piston fighters of the 20th century.