In the dynamic realm of aviation history, one aircraft stands out as a true pioneer of its time – the Convair B-58 Hustler. Tasked with flying at exceptional altitudes and achieving supersonic velocities, this marvel of engineering marked a significant milestone in the United States Air Force’s pursuit of innovation. Developed during the 1950s for the Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC), the B-58 Hustler redefined the concept of speed as a defense mechanism, becoming the first operational bomber capable of Mach 2 flights.

The B-58 Hustler’s impact transcended its era, embodying a series of revolutionary features that distinguished it from its contemporaries. Its distinct delta wing configuration, coupled with an advanced inertial guidance navigation and bombing system, elevated its capabilities to new heights. The utilization of a sleek “wasp-waist” fuselage and cutting-edge heat-resistant honeycomb sandwich skin panels in both wings and fuselage further showcased the aircraft’s trailblazing design philosophy.

Although celebrated for its innovations, the B-58’s slim fuselage came with trade-offs. This limitation necessitated external bomb storage in a two-component pod located beneath the fuselage. This innovative pod not only accommodated a nuclear payload but also housed supplementary fuel reserves and state-of-the-art reconnaissance equipment.

The Convair B-58’s aerodynamic prowess translated into exceptional performance milestones. The initial production model achieved supersonic flight, sustaining speeds beyond Mach 2 for over an hour. Impressively, even with a single refueling stop, the bomber covered 1,680 miles in a mere 80 minutes. This era-defining aircraft held sway between 1960 and 1970, setting 19 world records for speed and altitude while securing five distinguished aviation trophies.

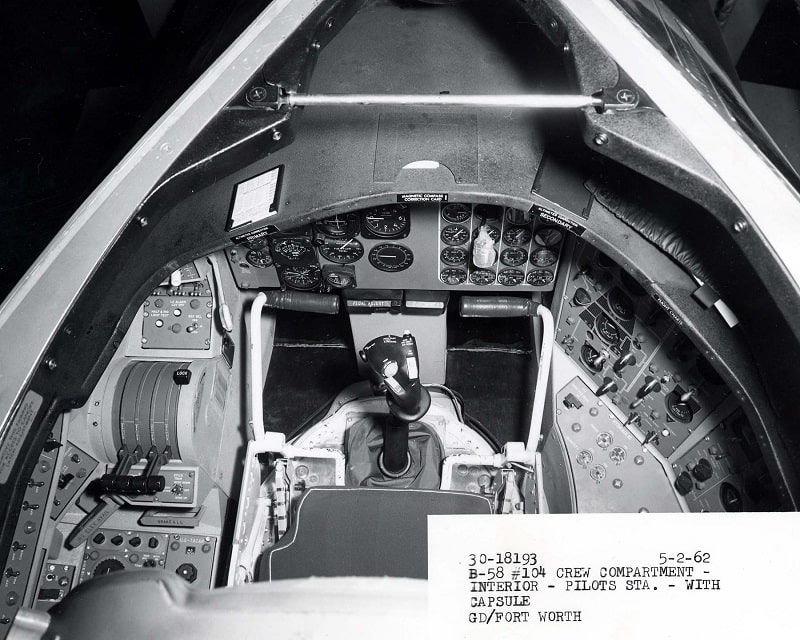

The B-58 Hustler’s crew arrangement was equally unconventional, comprising three distinct compartments – the pilot, navigator/bombardier, and defense systems operator each had their isolated workspace separated by equipment banks. Communication between these compartments was ingeniously facilitated through a string and pulley system along the cabin wall, allowing the crew to exchange notes and collaborate despite physical separation.

The aircraft’s velocity made interception by enemy fighters a daunting task, yet its vulnerability to catastrophic failures prompted critical safety enhancements. Initially outfitted with standard rocket-propelled ejection seats unsuitable for Mach 2 speeds, the aircraft underwent retrofitting with an encapsulated ejection system, significantly boosting crew survivability.

Despite its remarkable achievements, the B-58 Hustler faced setbacks in the form of tragic crashes, including two incidents at the Paris Air Show in 1961 and 1965, resulting in the loss of 26 aircraft and 36 crew members. Evolving strategic landscapes saw the B-58 transition from its high-altitude role to low-level-penetration missions due to the emergence of Soviet high-altitude surface-to-air missiles and supersonic fighters. However, operational costs and a limited combat range of 2,000 miles without refueling led to its relatively short service life.

Regrettably, the Hustler’s illustrious chapter came to a close on January 31, 1970, with its retirement after a mere decade of active duty. Despite its abbreviated service span, the B-58 Hustler continues to leave an indelible mark on aviation history. Several of the 116 units built have found a permanent home in museums across the country, including the iconic “Cowtown Hustler,” now displayed at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. The aircraft’s remarkable feats, including its record-setting Los Angeles to New York flight in 1962, live on, immortalized in the Cold War Gallery. In retrospect, the B-58 Hustler stands as a testament to human ingenuity, pushing the boundaries of aeronautical excellence and shaping the evolution of air power.